McCarthy, from Kinsale, County Cork, sailed with Shackleton in the 20ft-long boat James Caird for 16 days from Elephant Island to South Georgia in 1916 to get help for the rest of their shipmates from the Polar exploration vessel Endurance, who were stranded and running out of food in Antarctica. Shackleton and his crew of five put their own lives in imminent danger to save their comrades from a lingering death.

It remains one of the greatest maritime stories in history.

Shackleton later paid tribute to the Irishman in his memoirs writing:

"McCarthy, the best and most efficient of sailors, always cheerful under the most trying circumstances and who for these reasons I chose to accompany me on the boat journey to South Georgia."But tragically McCarthy, who had survived the perils of the southern ocean, was thrust into wartime service immediately he returned to Britain and was killed when his ship was sunk by a German submarine in 1917. He never lived to see his hard-earned Polar Medal.

"McCarthy was indomitable, a true hero and just the sort of man needed for a hazardous mission such as the voyage of the James Caird," says Pierce Noonan, a director of Dix Noonan Webb. "When handing over the tiller he always joked that it was 'a fine day' as the wind howled and the waves crashed around them. His natural optimism shone like a beacon throughout the voyage. Today his Polar Medal acts as a memorial to a sailor who survived Shackleton's expedition but not the slaughter of the First World War."

McCarthy's medal with the clasp 'Antarctic 1914-16' is the only bronze Polar Medal awarded for Shackleton's voyage in the James Caird. Shackleton himself and two men received the silver version of the medal, while two other crewmen were not recommended for any award. The McCarthy medal was in the possession of an Irish collector who is now deceased and has never been on the open market before.

Born in County Cork in 1885, McCarthy was an Able Seaman in the Royal Naval Reserve when he applied to join Shackleton's Antarctic expedition in 1914. He was one of just 26 men selected to crew the expedition's vessel Endurance. The aim was to cross the Antarctic continent, a journey of 1,800 miles, and the expedition was given permission to set sail in August 1914 despite the outbreak of the First World War. However by January 1915 Endurance was held up by solid pack ice in the Weddell Sea and in October of that year the ship, damaged by the pressure of the ice, was abandoned and later sank.

The crew established camp on an ice flow and in April 1916 embarked on a hazardous five days journey to Elephant Island in the James Caird and two other ship's boats. Once there it was clear that rescue would have to be sought because food supplies and the men's morale were both dwindling. Shackleton decided to undertake a dangerous 800-miles journey across one of the most tempestuous areas of water in the world to South Georgia, where he knew there were whaling stations. He selected McCarthy and four others and set off on 24 April 1916.

"The tale of the next 16 days is one of supreme strife amid heaving waters for the sub-Antarctic Ocean fully lived up to its evil winter reputation," Shackleton later wrote. "Cramped in our narrow quarters and continually wet from the spray, we suffered severely from cold throughout the journey. We fought the seas and winds and at the same time had a daily struggle to keep ourselves alive."

One of the crew, Frank Worsley, later recorded that when McCarthy had finished his time on watch at the tiller, he always displayed his "cheerful optimism and his habit of handing over the helm with 'it's a fine day, sorr'." After surviving a massive wave which threatened to overwhelm the James Caird, they reached South Georgia on 10 May 1916. Shackleton and two others set off to find the whaling stations, while McCarthy stayed behind to look after the other two crew members, who were in a weak condition. Both they and the rest of the crew of Endurance left behind on Elephant Island were subsequently rescued. McCarthy was sent back to Britain with Shackleton's warm expressions of gratitude but the authorities there showed little sympathy for his ordeal and almost immediately thrust him into service aboard the armed oil tanker S.S. Narragansett. The ship was torpedoed and sunk off the south-west coast of McCarthy's native Ireland on 16 March 1917 and he was one of 46 sailors who lost their lives. Shackleton later praised McCarthy saying that he was "killed at his gun".

Tragically McCarthy never lived to see his Polar Medal and his First World War medals were never claimed or issued. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial. A joint bust of McCarthy and his brother Morty, also an Antarctic explorer, was unveiled in Kinsale in September 2000.

FOOTNOTE

Timothy McCarthy (1885-1917) was the son of John and Mary McCarthy of Kinsale, County Cork. He was serving as an Able Seaman in the Royal Naval Reserve when he applied to join Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914. McCarthy was one of 26 men chosen to crew the Endurance for the expedition.

Little elaboration of this, one of the most famous of Polar expeditions, is required here. McCarthy's prominent role, however, is worthy of further illustration. After leaving home shores the Endurance was held up by solid pack ice in the Weddell Sea in January 1914. This was before Shackleton's trans-continental party could even reach its starting point. Prior to this occurrence common consensus amongst the whaling captains at Grytviken, South Georgia, with whom Shackleton had consulted, was that it was the worst year in living memory for currents and ice patterns. Shackleton had ploughed on regardless, and this indomitable spirit was to be tested countless times over the coming months.

Through January, and into February 1915, the ice continued to pack tightly around the Endurance as she drifted with the ice. It became apparent that the crew would have to winter with the ship in the ice. The pressure of the ice caused damage to the ship, and she began to leak. On 27 October 1915 the ship was abandoned and a camp set up on the ice. After a failed attempt to sledge to Robertson Island, another camp called Ocean Island was established on a large ice floe. As many supplies as possible were rescued and accumulated here before the Endurance eventually sank on the 21st November.

In December 1915 several reconnaissance journeys were carried out, but all were painfully slow due to the disintegrating ice. A new more secure camp was established some 10 miles from the old one. At Patience Camp the party waited for conditions to improve so that they may be able to use the three boats (Dudley Docker, James Caird and the Stancomb Wills) that they had with them. At the end of the first week of April 1916 Clarence Island and Elephant Island had been sighted. Shackleton realised with anxiety that beyond these islands there was no refuge. All this time the ice pack was breaking up and the situation becoming more fraught with danger. It was impossible at this juncture to use the boats, due to the risk of them being crushed in the ice.

Nonetheless it was imperative that action be taken and on the 10th April they embarked on their 5 day journey to Elephant Island. Conditions were perilous, 'a terrible night followed, and I doubted if all of the men would survive it. The temperature was below zero and the wind penetrated our clothes and chilled us almost unbearably. One of our troubles was lack of water, for we had emerged so suddenly from the pack into the open sea that we had not had time to take aboard ice for melting in the cookers, and without ice we could not have hot food. The condition of most of the men was pitiable. All of us had swollen mouths and could hardly touch the food... we were all dreadfully thirsty, and although we could get momentary relief by chewing pieces of raw seal meat and swallowing the blood, our thirst was soon redoubled owing to the saltiness of the flesh.' (South, The Story of Shackleton's Last Expedition 1914-17, refers).

Elephant Island - Wild and McCarthy Find a Base

Exhausted, Shackleton's men hauled their supplies on to an inhospitable landing place on Elephant Island. After a reconnaissance it was quickly apparent that the beach was unsuitable for a long term base. On the 16th April Shackleton decided to send a party, under Frank Wild, to find a more suitable site for a camp. The party was to be comprised from some of the more hardier individuals, and McCarthy was amongst them, 'I had decided to send Wild along the coast in the Stancomb Wills to look for a new camping-ground, on which I hoped the party would be able to live for weeks or even months in safety.

Wild, accompanied by Marston, Crean, Vincent and McCarthy, pushed off in the Stancomb Wills at 11am and proceeded westward along the coast... The Stancomb Wills had not returned by nightfall, but at 8pm we heard a hail in the distance and soon, like a pale ghost out of the darkness, the boat appeared. I was awaiting Wild's report most anxiously, and was greatly relieved when he told me that he had discovered a sandy spot, seven miles to the west... Wild said that this place was the only possible camping-ground he had seen, and that, although in very heavy gales it might be spray-blown, he did not think that the seas would actually break over it. The boats could be run on a shelving beach, and, in any case, it would be a great improvement on our very narrow beach.' (Ibid)

On the 17th April the three boats set off for the new site. The seven mile pull took most of the day, as they almost immediately encountered a gale on the open water. Most of the members of the Expedition were suffering severely from salt water boils, and to a slightly lesser extent frostbite. The new camp, however, appeared to offer relative safety for as long as the dwindling food supplies lasted.

The Greatest Open-Boat Voyage of All Time...

With the onset of winter near, however, it was clear that Shackleton had to do something. It was unlikely that there would be enough food for all of the men, and the latter were becoming weaker and more demoralised as the days went by. What ensued was to become one of the greatest open-boat voyages of all time:

'The conclusion was forced upon me that a boat journey in search of relief was necessary and must not be delayed. The nearest port where assistance could certainly be secured was Port Stanley, in the Falkland Islands, 540 miles away; but we could scarcely hope to beat up against the prevailing north-westerly wind in a frail and weakened boat with a small sail area.

It was not difficult to decide that South Georgia, which was over 800 miles away but lay in the area of west winds, must be our objective. I could count upon finding whalers at any of the whaling-stations on the east-coast, and, provided that the sea was clear of ice and that the boat survived the great seas, a boat party might make the voyage and be back with relief in a month.

The hazards of a boat journey across 800 miles of stormy sub-Antarctic ocean were obvious, but I calculated that at the worst this venture would add nothing to the risks of the men left on the island. The boat would not require to take more than one month's provisions for six men, for if we did not make South Georgia in that time we were sure to go under....

The perils of the proposed journey were extreme, and the risk was justified solely by our urgent need of assistance. The ocean south of Cape Horn in the middle of May is known to be the most tempestuous area of water in the world, and the gales are almost unceasing. We had to face these conditions in a small and weather-beaten boat, already strained by the work of the previous months.... I had at once to tell Wild that he must stay behind, for I relied upon him to hold the party together while I was away... I determined to take Worsley with me as I had a very high opinion of his accuracy and quickness as a navigator... Four other men were required, and, although I thought of leaving Crean as a right-hand man for Wild, he begged so hard to come that, after consulting Wild, I promised to take him.... I finally selected McNeish, McCarthy and Vincent, in addition to Worsley and Crean.... The crew seemed a strong one, and as I looked at the men I felt confidence increasing....

After the decision was made, I walked through the blizzard with Worsley and Wild to examine the James Caird. The 20-foot boat had never looked big, but when I viewed her in the light of our new undertaking she seemed in some mysterious way to have shrunk. She was an ordinary ship's whaler, fairly strong, but showing signs of the strain she had endured. Standing beside her, and looking at the fringe of the tumultuous sea, there was no doubt that our voyage would be a big adventure.

I called McCarthy [McNeish], the carpenter, and asked him if he could do anything to make the ship more seaworthy. He asked at once if he was to go with me, and seemed quite pleased when I answered "Yes." He was over fifty years of age and not altogether fit, but he was very quick and had a good knowledge of sailing-boats. He told me that he could contrive some sort of covering for the James Caird if he was allowed to use the lids of the cases and the four sledge-runners, which he had lashed inside the boat for use in the event of a landing on Graham Land at Wilhelmina Bay. He proposed to complete the covering with some of our canvas, and immediately began to make his plans.' (Ibid, in this account, written in 1919, Shackleton occasionally confuses McCarthy with McNeish, the latter was in his 50's whilst McCarthy was in his 20's)

The voyage commenced on 24 April 1916, 'the tale of the next sixteen days is one of supreme strife amid heaving waters, for the sub-Antarctic Ocean fully lived up to its evil winter reputation. I decided to run north for at least two days while the wind held, and thus get into warmer weather before turning to the east and laying a course for South Georgia.

We took two-hourly spells at the tiller. The men who were not on watch crawled into the sodden sleeping-bags and tried to forget their troubles for a period. But there was no comfort in the boat, indeed the first night aboard the boat was one of acute discomfort for us all, and we were heartily glad when dawn came.... Cramped in our narrow quarters and continually wet from the spray, we suffered severely from cold throughout the journey. We fought the seas and winds, and at the same time had a daily struggle to keep ourselves alive. At times we were in dire peril. Generally we were encouraged by the knowledge that we were progressing towards the desired land, but there were days and nights when we lay hove to, drifting across the storm-whitened seas, and watching the uprearing masses of water, flung to and fro by Nature in the pride of her strength.

Nearly always there were gales. So small was our boat and so great were the seas that often our sail flapped idly in the calm between the crests of two waves. Then we would climb the next slope, and catch the full fury of the gale where the wool-like whiteness of the breaking water surged around us.... Much bailing was necessary, but nothing could prevent our gear from becoming sodden... There were no dry places in the boat, and at last we simply covered our heads with our Burberrys and endured the all-pervading water. The bailing was work for the watch.

None of us, however, had any real rest. The perpetual motion of the boat made repose impossible; we were cold, sore and anxious. In the semi-darkness of the day we moved on hands and knees under the decking. By 6pm the darkness was complete, and not until 7am could we see one another under the thwarts.... The difficulty of movement in the boat would have had its humorous side if it had not caused so many aches and pains. In order to move along the boat we had to crawl under the thwarts, and our knees suffered considerably. When a watch turned out I had to direct each man by name when and where to move, for if all hands had crawled about at the same time the result would have been dire confusion and many bruises.' (Ibid)

During this testing period Worsley records that when McCarthy had finished his time on watch at the tiller, he always displayed his 'cheerful optimism' and his habit of handing over the helm with "It's a fine day, sorr."

By the seventh day, the weather finally started to improve to the extent that the party were able to calculate that they had travelled roughly over 380 miles towards South Georgia. Over the course of the following three days steady progress was made, despite increasing suffering caused by exposure and a diminishing supply of food.

On the eleventh day, 5th May, the weather changed for the worse, 'a hard north-westerly gale came up... The sky was overcast and occasional snow-squalls added to the discomfort produced by a tremendous cross-sea - the worst, I thought, which we had encountered. At midnight I was at the tiller, and suddenly noticed a line of clear sky between the south and the south-west. I called to the other men that the sky was clearing, and then, a moment later realised that what I had seen was not a rift in the clouds but the white crest of an enormous wave.

During the twenty-six years' experience of the ocean in all its moods I had never seen a wave so gigantic. It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite apart from the big white-capped seas which had been our tireless enemies for many days. I shouted, "For God's sake, hold on! It's got us!" Then came a moment of suspense which seemed to last for hours. We felt our boat lifted and flung forward like a cork in breaking surf. We were in a seething chaos of tortured water; but somehow the boat lived through it, half-full of water, sagging to the dead weight and shuddering under the blow. We bailed with the energy of men fighting for life, flinging the water over the sides with every receptacle which came into our hands; after ten minutes of uncertainty we felt the boat renew her life beneath us. She floated again, and ceased to lurch drunkenly as though dazed by the attack of the sea. Earnestly we hoped that never again should we encounter such a wave.' (South, The Story of Shackleton's Last Expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton refers)

McCarthy First to Sight South Georgia

Privations continued among the men, with Vincent having collapsed under the strain and water now running desperately low. The 6th and the 7th May, 'passed for us in a sort of nightmare. Our mouths were dry and our tongues swollen. The wind was still strong and the heavy sea forced us to navigate carefully. But any thought of our peril from the waves was buried beneath the consciousness of our raging thirst... Things were bad for us in those days, but the end was approaching. The morning of May 8th broke thick and stormy, with squalls from the north-west. We searched the waters ahead for a sign of land, and, although we searched in vain, we were cheered by a sense that our goal was near. About 10am we passed a little bit of kelp, a glad signal of the proximity of land. An hour later saw two shags sitting on a big mass of kelp, and we knew then that we must be within ten or fifteen miles of the shore.... We gazed ahead with increasing eagerness, and at 12.30pm, through a rift in the clouds, McCarthy caught a glimpse of the black cliffs of South Georgia, just fourteen days after our departure from Elephant Island. It was a glad moment. Thirst-ridden, chilled, and weak as we were, happiness irradiated us. The job was nearly done.' (Ibid)

On the 10th of May, despite being tormented by one last hurricane, the James Caird finally managed to land in a small cove, with a boulder strewn beach guarded by a reef on the south side of King Haakon Bay. The crew had not drunk anything for 48 hours. Completely exhausted, and unable to pull the boat out of the water they landed their stores and rested for a few days in a cave. They hunted for birds, and slowly recuperated some strength thus enabling them to embark again on the 15th May for the 8 mile trip to King Haakon Bay.

Shackleton's men arrived at the head of the bay, and proceeded to establish Peggotty Camp under the beached and upturned boat. From here it was decided that Shackleton, Worsley and Crean would set out on foot for Stromness Bay, and the whaling stations. On the evening of the 18th May, 'we turned in early that night, but troubled thoughts kept me from sleeping. The task before the overland party would in all probability be heavy, and we were going to leave a weak party behind us in the camp. Vincent was still in the same condition and could not march. NcNeish was pretty well broken up. These two men could not manage for themselves, and I had to leave McCarthy to look after them. Should we fail to reach the whaling station McCarthy might have a difficult task.' (Ibid)

On the 19th May the three men set off to cross the mountains to Stromness. They managed the journey, despite their weakened state, by the following day. They had traversed a completely unexplored mountain range. Worsley set off in a whaler to rescue McCarthy and his two charges that night. They returned to Stromness on the 22nd May, 'McCarthy, McNeish and Vincent were landed on the Monday afternoon, and quickly began to show signs of increasing strength under a regime of warm quarters and abundant food. McCarthy [McNeish] looked woefully thin after he had emerged from a bath. He was over fifty years of age and the strain had told upon him more than upon the rest of us. The rescue came just in time for him.' (Ibid)

Shackleton arranged for McNeish and Vincent to be returned to England. He also arranged passage for McCarthy to be sent home, with both his and Worsley's warm expressions of gratitude.

The Great War - Ultimate Sacrifice

Whilst Shackleton eventually rescued the rest of his men from Elephant Island, McCarthy, who had barely survived the ordeals of the Antarctic was almost immediately thrust into service during the Great War. He returned to the Royal Naval Reserve, and served as a Leading Seaman in S.S. Narragansett. She was a defensively armed British Steam Tanker, and on the 16th March 1917 was employed on a voyage from New York to London transporting lubricating oil. On the latter date she was torpedoed and sunk by U-44 off the south-west coast of Ireland. Forty-six sailors lost their lives, including McCarthy.

As Shackleton remarked himself of his crew, 'The same energy and endurance which they showed in the Antarctic they brought to the Greater War in the Old World. And having followed our fortunes in the South it may interest you to know that practically every member of the Expedition was employed in one or other branches of the active fighting forces during the war. Of the fifty-three men who returned out of the fifty-six who left for the South, three have since been killed and five wounded. McCarthy, the best and most efficient of sailors, always cheerful under the most trying circumstances, and who for these reasons I chose to accompany me on the boat journey to South Georgia, was killed at his gun in the Channel.' (Ibid)

Tragically McCarthy never lived to see his hard earned Polar Medal, nor does it appear from the roll that his Great War medals were ever claimed or issued. He is commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial.

Note: Neither McNeish nor Vincent were recommended by Shackleton for the Polar Medal and neither received it. Thus, of the six gallant men of the James Caird, Shackleton, Worsley and Crean received Silver medals or clasps, whilst McCarthy alone received the Bronze medal and clasp.

The James Caird, named after one of the sponsors of the expedition, survives to this day and is proudly displayed at Dulwich College, South London.

Source: Dix Noonan website.

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

FRANK WILD'S MEDALS

The Unique and Historic Polar Medal to Commander Frank Wild,

by Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

July 9, 2009

Through the kindness of Robert Stephenson, Coordinator of the website The Antarctic Circle, and polar book author Angie Butler, I have been corresponding and speaking with the family of Commander John Robert Frances "Frank" Wild, RNVR, CBE, FRGS (1873-1939).

When his widow died in 1970, Frank Wild's British War Medal and Victory Medal (LIEUT. F. WILD, R.N.V.R.), geographical society medals, British National Antarctic Expedition Sports Medal (FRANK WILD), and a dress miniature Polar Medal with clasps Antarctic 1902-04 & Antarctic 1907-09, along with a quantity of original documentation, were sold at Sotheby's in June 1971. They were last sold at Dix Noonan Webb on Dec. 13, 2007, and are now part of a London physician's collection.

It has been known for many years that Wild's unique Polar Medal with clasps Antarctic 1902-04, Antarctic 1907-09, Antarctic 1912-14 and Antarctic 1914-16, remained with his family in South Africa. The medal was issued officially engraved: A.B. F. WILD. "DISCOVERY". Only two four-clasp Polar Medals have ever been issued, the other being to Ernest Joyce, featuring the clasps Antarctic 1902-04, Antarctic 1907-09, Antarctic 1914-16 and Antarctic 1917. Joyce also received a duplicate medal and both medals are known to exist.

Wild's Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE, New Year Honours List, 1920) and dress miniature medals accompany his Polar Medal. The miniatures are mounted for wear: CBE, Polar Medal with 4 clasps, British War Medal, Mercantile Marine War Medal and Victory Medal.

Wild's family sought my advice concerning parting with the medals, since various interested parties in South Africa and the UK have attempted to acquire them over the years. I strongly recommended the best way to preserve Frank Wild's memory and the medals' provenance was to auction them through a leading London firm, and recommended Dix Noonan Webb. Consequently, the family has informed me that the CBE, Polar Medal and miniatures will be offered in the rooms of DNW (September 17-18, 2009).

Frank Wild had more Antarctic experience than anyone else during the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration (1895-1922), participating in five expeditions between 1901 and 1922. Wild's work and leadership were universally respected by his Antarctic comrades, who virtually never had a critical word to say or write about the Skelton, Yorkshire native.

Wild first went to Antarctica as an Able Seaman with Scott during the British National Antarctic Expedition of 1902-04, having had 12 years in the merchant navy before joining the Royal Navy in 1900. He took part in several sledge journeys, including the tragic first attempt to reach Cape Crozier. His spirited leadership brought several men back to the ship after the death of Able Seaman George Vince, who drowned after slipping down a steep ice slope during a blizzard. Scott thought highly of Wild's service and specially mentioned him in despatches, thus Wild was duly promoted to petty officer. During the expedition, Wild struck up a friendship with the third lieutenant, Ernest Shackleton.

As a member of Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition (1907-09), Wild was placed in charge of provisions, and was one of the four-man sledge party to reach just 97 miles from the South Pole. Fellow Yorkshireman and expedition geologist Douglas Mawson afterwards wrote that his experiences during this time, "acquainted me with Wild's high merits as an explorer and leader." Upon his return, Frank Wild left the Royal Navy by purchase.

Though Scott asked Wild to join his second Antarctic venture, Wild declined, as he felt Scott was "too much the navy man." Instead, he joined Mawson's 1912-14 Australian Antarctic Expedition as a sledging expert and was appointed leader of the Western Base. Under him were seven untried men—none had previously served in the polar regions. In spite of terrible sledging conditions, Wild led successful sledge parties to open up a new region, Queen Mary Land.

Wild then played a vital role as second-in-command of the Endurance during the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17. After the ship sank, the men made their way by sledge and boat to land on the desolate Elephant Island. Here, Wild's leadership abilities were tested to the fullest, as he was left in charge while Shackleton went on his epic boat journey to get help on South Georgia. Wild never gave up hope that Shackleton would return to rescue them, and whenever the sea ice cleared, he would say, "Roll up your sleeping-bags, boys: the boss may be coming today."

On returning home, Wild volunteered for duty and was made a Temporary Lieutenant, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. After a Russian language course, he became the RN transport officer at Archangel, superintending arriving war materials during the Allied Intervention in Russia.

After the war, Wild went to South Africa where he farmed with two former Antarctic comrades. They worked the soil in British Nyasaland until 1921, the beginning of Wild's final Antarctic adventure. They cleared the then virgin forest and planted cotton, and loved the life, though suffering from intermittent bouts of malaria.

From 1921-22, Wild was second-in-command of the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition, a poorly-equipped venture, with no clear plan, and a small ship—the Quest. Shackleton died of a heart attack on South Georgia, and Wild took over and completed the journey, combating unfavorable weather to Elephant Island and along the Antarctic coast.

He returned to South Africa to continue to farm. Frank Wild died on Aug. 19, 1939, in Klerksdorp, where he was employed as a storeman at the Babrosco Mine. He was cremated on the Aug. 23, 1939, in the Braamfontein Cemetery in Johannesburg.

Frank Wild's younger brother was also a polar explorer. Petty Officer Harry Ernest Wild, RN, looked after the stores and dogs of the Ross Sea Party during the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Harry Wild died of typhoid in 1918, and in 1923 was posthumously awarded the Albert Medal (Second Class/Land) for the expedition. His Albert Medal, Polar Medal with clasp Antarctic 1914-16 and Italian Messina Earthquake Medal (1908) exist together, while his First World War Memorial Plaque is known in a separate collection. H.E. Wild was also entitled to the Antarctic 1917 clasp, and though sent to brother J.R. Wild in 1921, it was never attached to his Polar Medal.

Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

Veteran of Five Heroic Age Antarctic Expeditions

Florida, USA

Left: Wild's Commander of the Order of the British Empire and Polar Medal with four clasps.

Right: Wild's miniature medals.

(Courtesy Dix Noonan Webb, auctioneers, London)

ANTARCTIC FIDELITY REWARDED: SERGEANT WILLIAM CUNNINGHAM, ROYAL MARINES

To reproduce or distribute, visit: gmsteinfrgs.icopyright.com

In April 2009, Captain Richard Campbell, OBE (RN), published The Voyage of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror to the Southern and Antarctic Regions. Captain James Clark Ross, R.N. 1839-1843. The Journal of Sergeant William K. Cunningham, R.M. of HMS Terror in the online Hakluyt Society Journal,

Log on to our new website dedicated to the school: http://www.hakluyt.com/journal_index.htm?PHPSESSID=970a2409768b33fb1cf6e18975c7f52a

I had long been aware of this very important Antarctic document, and afterward corresponded with Captain Campbell, applauding his splendid work in bringing it to the public stage.

The exemplary conduct of Serjeant [Samuel] Baker of this ship [Erebus] and of Serjt. Cunningham of the Terror, during a period of four years of arduous service in the Antarctic Regions, requires that I should make an especial application to you in their favour. More deserving or better conducted non-commissioned officers I have never known. . . I beg leave particularly to solicit for the Serjeants your favourable consideration of their services, and that you will afford them any advancement or privilege which it may be in your power to bestow and which, I assure you, they have well merited.

Cunningham was subsequently advanced to Color Sergeant, and then to Quarter Master Sergeant in 1846. But I wondered if the Captain's felicitous scribbles would translate into tangible rewards for his Marine sergeants? As I pondered the possibilities, the Royal Marines MSM soon came sharply into focus.

The story of this sparingly awarded medal can be traced to the Army during the final month of 1845, during which time a Royal Warrant authorized the issue of a medal, with annuity (annual allowance), for meritorious service to serving sergeants. The following year, it was suggested the Treasury should extend this honor to Her Majesty's maritime infantry, but nothing came of this until an Admiralty Circular in January 1849. At that time, £250 was made available for annuities '"for distinguished or meritorious service", to Sergeants who are now, and who may be hereafter, in the service, and such annunities are to be enjoyed either while the sergeants are serving on shore, or after their discharge with Pension, in sums not exceeding £20 a year.'

In consulting the writings of naval historian Captain Kenneth Douglas-Morris, his article titled 'The Meritorious Service Medal for Royal Marines History and Roll: 1849 to 1884' revealed that Cunningham was awarded the medal in 1854. And there it was—for a second time, Cunningham's superiors took advantage of the opportunity to reward him with 'any advancement or privilege which it may be in [their] power to bestow'.

I next acquired Cunningham's service papers, which state: 'Received the Honorary Medal and a Gratuity of £15 for Long Service and Good Conduct 19th January 1852. Awarded the Honorary Medal and an Annuity of Ten Pounds as a reward for Meritorious Service 15th Feby 1854.' (ADM 157/21) In fact, he was invalided from the service only four months later.

The identity of Cunningham's MSM is unmistakable, since it is an extremely rare type, and was issued officially engraved on its edge: 'QR. MR. SERGT. WM. KEATING CUNNINGHAM, CHATHAM DIVN. R.M. 30: JAN: 1854'. (Spink) In addition, he was the first RM sergeant to receive an MSM on the death of another recipient. (Bilcliffe to Stein, Oct. 25, 2005)

Douglas-Morris knew Cunningham's MSM survived the ravages of time—but where was it now? Between 1999 and 2004, I hunted the medal, beginning at a medals convention, through a dealer, and finally at auction—but each time, that historic scrap of silver slipped through my fingers. Then, in the summer of 2006, my casual perusal of a Glendining's catalogue spun the clock a century backwards: Cunningham's MSM and LS&GC were sold as a pair on Wednesday, Feb. 5, 1902 (lot 605), £4, 5 shillings. Surely the LS&GC also survives to this day. Strikingly, at no time during the several offerings was there any hint of Cunningham's Antarctic service.

Sadly, Sergeant Baker did not receive a much-deserved MSM, and though one might conjecture as to the reason why, any such guesswork may cast an unwarranted shadow on this man's memory. With or without medallic recognition, Sergeant Samuel Baker honorably carried out his duties in frozen seas.

On a more positive note, from the start of my wonderings, William Cunningham's reference to his 'dearly beloved friend Sergt Kelly' sent me searching for a possible connection among the names in Douglas-Morris' LS&GC Medal listings. One individual quickly rose to the surface: Color Sergeant Jeremiah Kelly, Chatham Division (the same as Cunningham). His LS&GC (Anchor Type) was issued in 1843, and was last recorded as being sold at Sotheby's, June 23, 1972. Captain Campbell kindly confirmed my strong suspicion that the two Kellys were indeed one and the same.

(Letter book of HMS Erebus; Letter No. 370, Sept. 22, 1843)

Picture Credits:

Cunningham's Royal Marines Meritorious Service Medal (courtesy of Spink).

Erebus and Terror pushing through the pack during a fog in January 1842. (Sir J.C. Ross' narrative, Vol. 2)

Acknowledgements:

John Bilcliffe

References:

Captain Richard Campbell, OBE (RN)

Gale Hawkes

G.W. Hawkes, Ph.D.

Peter John

T.F. Minneice

D.A.E. Morris

David J. Scheeres

Jerome K. Voigt

Copy letter book of HMS Erebus. Ross Family Papers.

Cunningham, W.K., Attestation for the Royal Marines (ADM 157/21). The National Archives.

Cunningham, W.K. Diary of Sergeant Cunningham, Royal Marines, H.M.S. Terror. Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (ref. no. D869).

Douglas-Morris, Capt. K.J. 'The Meritorious Service Medal for Royal Marines History and Roll: 1849 to 1884'. OMRS Journal, Vol. 13, No. 4, Winter 1974.

_________________. 1987. Naval Medals 1793-1856. London: privately printed.

_________________. 1991. The Naval Long Service Medals 1830-1990.

London: privately printed.

Glendining's. Feb. 5, 1902.

Liverpool Medal Company. September & November 1999.

McInnes, I. 1983. The Meritorious Service Medal to Naval Forces. Chippenham: Picton Publishing.

Muster Book for HMS Erebus, 8 April 1839-23 September 1843 (Admiralty ADM 38/8045). The National Archives.

Muster Book for HMS Terror, 11 May 1839-23 September 1843 (Admiralty ADM 38/9162). The National Archives.

Ross, Capt. Sir J.C. 1847. A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions During the Years 1839-43. (Volumes 1 & 2). London: John Murray.

Ross, M.J. 1982. Ross in the Antarctic: The Voyages of James Clark Ross in Her Majesty's Ships Erebus & Terror 1839-1843. Whitby: Caedmon of Whitby.

Sotheby's. June 23, 1972.

Spink. Nov. 30, 2004.

MEN OF BRONZE: NETMEN OF THE ANTARCTIC,

PRESERVERS OF LIFE IN THE SOUTHERN OCEAN

All rights reserved.

As early as 1917, it was recognized that the leviathans of the oceans were in danger of being hunted to extinction. A British Government interdepartmental committee was set up to review the excesses of the whaling industry, which then flourished in the Antarctic. However, it was not until 1923 that a committee with the required finances and authority was established to make 'a serious attempt to place the whaling industry on a scientific basis.'

The key to any operation of this magnitude was gaining control of whale catching, thus avoiding the depletion of whale stocks. But effective control was out of reach for one simple reason: not enough was known about the habits of whales, their distribution and migration, or of their main food—the 4-6 cm.-long shrimp known as krill.

George Ayres and Duncan Kennedy were two individuals intimately connected with catching krill—after all, they were netmen. They became part of an historic scientific program which spanned over a quarter-century, resulting in the award of white-ribboned decorations formed in that deceptively humble medal of bronze.

A netman was a petty officer responsible for the operation of various-sized nets used to collect marine specimens. Long hours were dedicated to raising and lowering these spider webs in all variety of weather and seas—demanding endurance of mind and body, and causing agony to the fingers.

Initially, Scott's former ship, Discovery, was purchased by the newly named Discovery Committee. Then in 1926, the steam vessel William Scoresby was built for the Committee and joined the effort, tasked with general oceanographic work, commercial scale trawling and whale marking experiments.

However, it was decided to replace Discovery with a new steel ship, specially built for an indefinite and ambitious series of scientific studies called the Discovery Investigations. The Royal Research Ship Discovery II carried a great deal of scientific and other research equipment, and to meet unknown conditions, her construction required careful planning and original thought. To expend large sums of money at all on serious long-term scientific research was admirable enough, but when one considers the international financial crisis of the early 1930s, this points to the vital importance of this scientific program.

Not all eyes were focused on science; amidst a web of political intrigue surrounding the Southern Continent, the old Discovery headed south again as part of the separate British-Australian-New Zealand-Antarctic Expedition (BANZARE). Norway, France and the United States had been gaining interest in the polar lands, and adjacent waters (filled as they were with seals and whales)—and territorial claims were also at stake.

Londoner George Ayres sailed across the Antarctic threshold with the BANZARE; though the 31-year-old Great War merchant navy veteran signed on as Able Seaman, he was elevated to Netman during the expedition. And he sailed in good company—onboard as Photographer was Endurance veteran Frank Hurley. The Australian was described by a former shipmate as 'a warrior with his camera, [who] would go anywhere or do anything to get a picture'. It was not empty praise either.

The BANZARE took place over two southern summers (1929-30 & 1930-31) and sought to chart large areas of coastline, make landings to plant the flag, and carry out inland surveys using a floatplane. In addition, the voyagers were tasked with hydrographic surveys, studies in meteorology, geology and fauna—especially the numbers, species and distribution of whales.

In 1934 Ayres received the Polar Medal with clasp ANTARCTIC 1929-31 for his recent contributions to polar exploration, but by this date he was well into further Antarctic adventures with shipmate Duncan Kennedy.

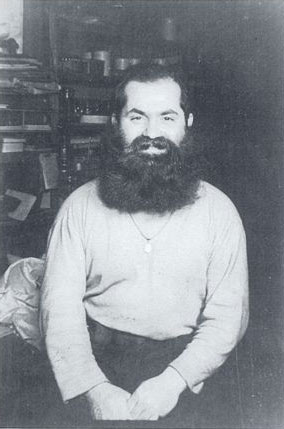

Kennedy was a Scot, born at Greenock toward the end of the first month in 1888. Not unusually, he took up the fishing trade, and eventually bore a scar in the center of his forehead as a probable reminder of many difficult days at sea. During the First World War Kennedy served in the Pilotage Service and received the British War Medal and Mercantile Marine War Medal. When he joined the RRS Discovery II in 1929, given his fishing background, it seemed only natural that he was rated a Netman.

In December, as Discovery II stood ready at London's St. Katherine's Dock, she received a visit from the King of Norway, who possessed a keen knowledge of everything to do with whaling. The beginning of her three-year odyssey was captured by an Oxford Mail reporter:

Hundreds of People gathered to witness the departure of the vessel and after two hours' skilful maneuvering she was steered into the Thames, where much larger crowds were watching.

At 234 feet long, and displacing 2,100 tons, Discovery II was only a fraction of the size of the 10-12,000 ton whaling factory ships active in Antarctic waters. Still, up until that time, she was the largest research ship ever to explore the Southern Ocean; for both the scientists and crew, it took time to get used to a new ship under conditions of intense cold, storm and pack ice. In addition, working the instruments and winches required constant practice. The surveys, biological collections and hydrographic work were more comprehensive than ever before attempted in southern waters.

The silk nets used for collecting sea plants and animals and were of six different sizes and mesh. The mouth of one tow net was the size of a dinner plate, while another was believed to be the largest in the world—so big that a man could stand upright inside it.

Each vertical net had a silk bag and it was lowered on a wire to whatever depth was being fished, and when a sample of the life in that layer had been obtained the mouth was cloased by a messenger, a weight that travelled down the wire and closed the mouth, trapping the contents—an operation that kept two scientists and a deck hand busy for two hours and often a great deal longer at each daily station.

While carrying out these duties during the agreeable weather of the sub-tropical zone, getting a soaking in one's short-sleeved shirt and shorts mattered little, but in Antarctic waters, climatic conditions convinced everyone Hell had indeed frozen over. Discovery II was transformed into a Christmas tree by a combination of gale and freezing seas that sprayed the ship's deck, bulwarks and upper works, thickly encrusting them with ice. Torches of burning waste and paraffin were sometimes necessary to thaw the blocks and sheaves over which ran the wires used to lower nets and instruments into the sea.

Under such difficult conditions, a sense of humor was a valuable asset onboard and greatly appreciated by all. Official Photographer Alfred Saunders grinned at Duncan Kennedy's amusing ways of speech:

As the ship glided from her berth girls crowded to the windows of the factories overlooking the dock and waved good-bye to the crew.

One very pretty girl, more daring than the rest, climbed out on to a ledge and shouted 'A Merry Christmas next week,' and the sailors responded with a cheer.

He had a persistent but unwitting habit of mispronouncing names. One of his jobs was to look after chemical and other scientific stores in the hold. To him sulphuric acid became 'sulfricated acid', hydrochloric acid became 'hydraulic acid', and formalin became 'formamint'. Once when he met a sailor who had had a violent fall on deck still walking about, he said that he thought he had 'discolated' his leg.

In these brief writings, it is impossible to do justice to the many achievements and adventures of the steel explorer and those who served aboard her. However, the drama of one particular incident during the second commission (1931-33) deserves a spotlight. It was during this period that Discovery II became the fourth vessel to circumnavigate Antarctica, and the very first to accomplish this feat in wintertime.

In January 1932, the ship was on her initial voyage deep into the Weddell Sea—the first steel ship to penetrate those waters and the sixth vessel of any type. Near where Shackleton's Endurance began meeting ice in 1916, Discovery II was caught in a frozen trap and her hull and rudder sustained damage (including a leaking starboard fuel tank).

At one point, on January 26, the captain wrote, 'Scientific staff and all spare hands employed this day poling ice floes clear of rudder and propeller.' Only with great difficultly was the ship extricated from her perilous situation.

In spite of such danger, the wholly natural surroundings never failed to make a marked impression on one's senses. William Peachey, who served from 1931-35 as a fireman/greaser, declared solemnly in a 1991 interview: 'it is impossible to describe the stillness and the quietness in the Antarctic, not a sound to be heard.'

During Discovery II's third commission (1933-35) her crew made a major impact on Admiral Byrd's Second Antarctic Expedition. On February 5, 1934, Byrd was faced with a severe crisis. Plagued with high blood pressure, his only doctor would have to go home on the support ship Jacob Ruppert, leaving only a single medical student. Byrd could not even consider keeping 95 men in the Antarctic with no doctor, and later wrote, 'I determined then to get a doctor, or else cancel the expedition.'

The previous month, Byrd had been surprised to hear the British ship's radio operator tapping out morse messages on the airwaves. Not that far from each other, the two expeditions exchanged greetings. Now, with an acute crisis at hand, Byrd fired off a radiogram to the captain of Discovery II, then at Auckland replenishing her supplies. In the end, New Zealander Dr. Louis Potaka sailed onboard to rendezvous on February 22 with Byrd's Bear of Oakland in the Ross Sea—the American expedition was saved!

Up until the end of this commission, Ayres was serving as an able seaman on Discovery II, but with Kennedy's departure from the ship in 1934, he was promoted to the familiar position of Netman. In spite of not yet reaching his 40th year, Ayres was a man of the days of canvas, when iron men sailed wooden ships; he hated fuss and 'liked to go quietly and efficiently' about his job. Saunders painted an image of the man and his work:

Ayres became the right-hand man of the scientific staff; conscientious and ever-willing, he performed a multitude of jobs. He kept the scientific equipment and chemicals of all kinds safely stowed in the hold and knew where everything was to be found. He was always mending the nets used for towing, and was always present on stations. His average working day was about sixteen hours, yet he was always helpful and cheerful. When walking along the deck during a station, one could hear him joking with his companions if the din of a raging storm permitted. Only if things went wrong did the tone of his voice change. He sometimes regaled us with numerous sea shanties which he sang at the top of his voice. He was a bachelor, wedded only to the sea.

After two more fruitful voyages, the onset of the Second World War prevented Discovery II from venturing into the Southern Ocean during those tumultuous years—bringing an end to an era for the men of bronze.

All told Kennedy served through six Antarctic seasons and received a well earned Polar Medal sporting the uniquely dated clasp ANTARCTIC 1929-34. At the start of the Second World War, he was Boatswain of HMS Alice, and when The London Gazette announced his Polar Medal two years later, Kennedy was still serving with this rank. Meanwhile, George Ayres was doing duty as an Able Seaman when the same Gazette heralded the ANTARCTIC 1931-39 clasp to his medal, representing in total 11 seasons in the southern Frozen Zone.

Of a mere 82 bronze Polar Medals and four individual clasps issued for Antarctic research between 1925 and 1939, only two netmen were so honored. Ayres' decoration was just one of eight medals representing two separate awards (including four medals with dates on the rims and single clasps).

The engraved naming in serifed capitals displays the recipients' full names. In cases of naval officers, abbreviated ranks and post nominals were included; for scientists, post nominals were also featured in the naming. Regrettably, ratings and the ships' details were not placed on the edge.

During 1950-51 (on her sixth commission) Discovery II sailed to the Antarctic one last time; so too did the William Scoresby, on her eighth commission. A few years later the Scoresby was sent to the ship breakers. Discovery III replaced her hardworking predecesor in 1962, and the latter was broken up the following year.

By 1963, the greatest scientific effort in the history of exploration had accumulated research filling 34 volumes: without the detailed research of the Discovery Committee, its scientists and sailors, no whale conservation would have been possible.

During interviews of Antarctic veterans for his book, John Coleman-Cooke was overwhelmed by the Frozen Zone's effect on its human intruders:

How then does it come about that every man who has visited the south polar seas always refers to it as the greatest of life's experiences? Everyone with whom the writer has discussed this stressed the powerful hold over the imagination of vast oceanic regions with the frozen, deserted continent to the south and the phenomena of the Southern Lights, ice patterns, daylight round the clock at one time of the year and almost total darkness at another. "It is a world apart," said one man, and that sums it up.

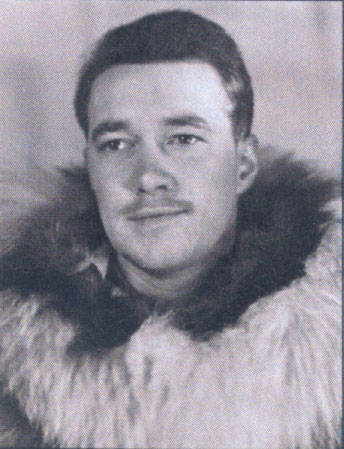

George Ayres on his 1920 Mercantile Marine identity certificate. (Identity Certificates (CR.10), Mercantile Marine Records, The National Archives)

Discovery II in the pack ice. (National Institute of Oceanography library)

The high-speed net used to catch krill. (National Institute of Oceanography library)

Handling a tow net on Discovery II. (Alfred Saunders, FRPS)

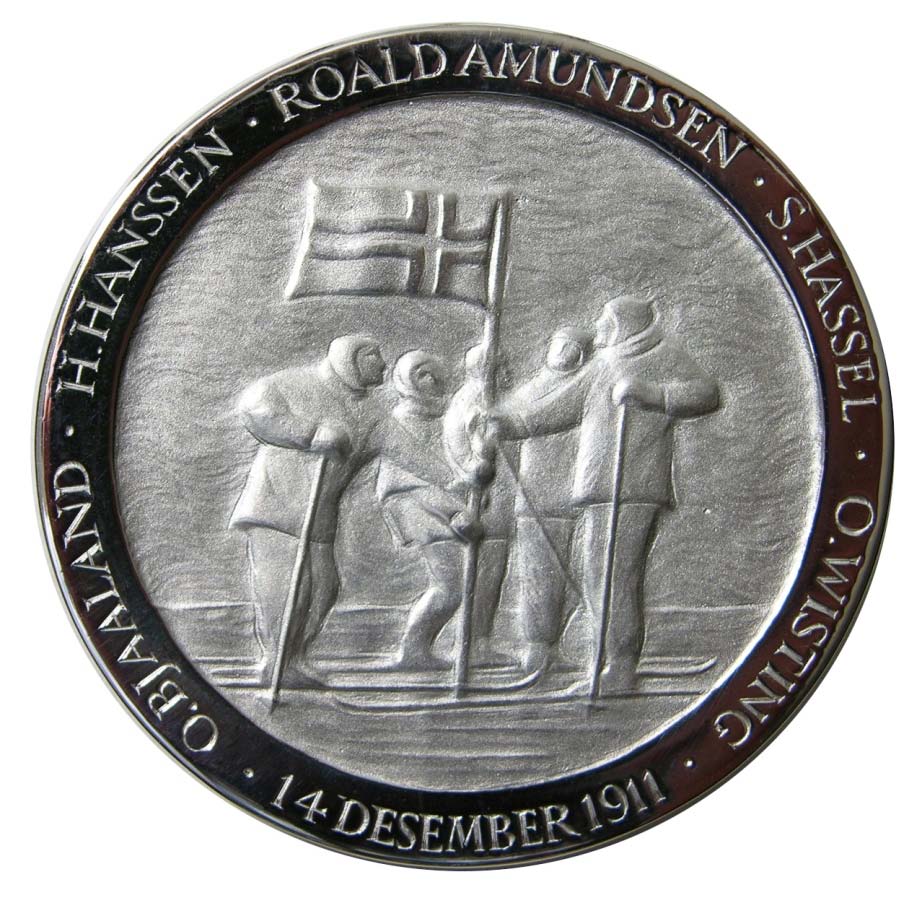

Bronze Polar Medal/Antarctic 1929-34 awarded to Duncan Kennedy, Netman, RRS Discovery II. (Courtesy Dix Noonan Webb, auctioneers, London)

Acknowledgements:

Kevin J. Asplin

References:

Keith Metcalfe

William A. Peachey

Coleman-Cooke, John. 1963. Discovery II in the Antarctic: The Story of British Research in the Southern Seas. London: Odhams Press Ltd.

Cornish, Richard. 'New Merchant Navy Records at the P.R.O.,' The Life Saving Awards Research Society Journal 30 (June 1997): 79.

The London Gazette (May 1, 1934 & October 7, 1941).

Jacka, Fred & Jacka, Eleanor (editors). 1988. Mawson's Antarctic Diaries. Sydney: Allen & Unwin Australia.

Mercantile Marine Medal Index Cards (CR.1, CR.2 Cards); Identity Certificates (CR.10). Mercantile Marine Records, The National Archives.

Metcalfe, Keith Interview with Mr. William Arthur Peachey, Fireman/Greaser, RRS Discovery II, 1931-35. (June 9, 1991).

Muster Book of RRS Discovery (BT 100/350). Board of Trade Records, The National Archives.

Ommaney, Francis D. 1938. South Latitude. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

Poulsom, Lieut. Col. Neville W. & Myres, Rear Adm. J.A.L. 2000. British Polar Exploration and Research: A Historical and Medallic Record with Biographies 1818-1999. London: Savannah Publications.

___________________ 'Polar Medal Statistics,' OMRS Journal 42 (December 2003): 266-270.

Reader's Digest. 1990. Antarctica: The Extraordinary History of Man's Conquest of the Frozen Continent. Surry Hills: Reader's Digest.

Rice, Tony. 1986. British Oceanographic Vessels 1800-1950. London: The Ray Society.

Saunders, Alfred. 1950. A Camera in Antarctica. London: Winchester Publications Ltd.

'Setting Out on Antarctic Voyage,' Oxford Mail (December 1929).

Yelverton, David E. 'The First Environmental Campaign Medal: the bronze George VI Polar Medal' (Parts I & II), Medal News (April 1989): 11-13 & (May 1989): 15-18.

Yelverton, David E. 'The Bronze George VI Polar Medal: a surprising find,'

Medal News (October 1989).

MEDALS AND DECORATIONS OF THE FRENCH

SOUTH SEAS & ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION, 1837-40

To reproduce or distribute, visit: gmsteinfrgs.icopyright.com

The French claim, with some justice, that Dumont d'Urville can rank with James Cook, the greatest navigator of them all. Like Cook he made three voyages round the world and important contributions to all the sciences, most of which were then in their lusty infancy.

—Helen Rosenman, translator and editor

of D'Urville's accounts of South Seas voyages

Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville was born in Normandy in 1790, and his childhood saw the development of a keen intellect that served the makings of a future explorer. A lifelong passion for the study of languages first showed itself so early that by the age of ten d'Urville was fluent in Latin. Past voyages of discovery were also on the boy's mind and he devoured volumes about Cook, Anson and Bougainville. At 17, d'Urville joined the French Navy, but the service had fallen into disrepair after its defeat at Trafalgar and the Royal Navy's blockade kept French ships in port.

Not being one to waste time, d'Urville filled the void of inactivity by studying languages. At this time, he penned his motivations for joining the navy:

I found that nothing was more noble and worthy of a generous spirit than to devote one's life to the advancement of knowledge. There was this feeling that my interests were pushing me towards the navy of discovery rather than the purely fighting navy. Not that I was afraid of battle, but my naturally republican spirit could not envisage any real glory attached to the act of risking one's life and killing one's fellow men for differences of opinions over things and words.

By 1810, d'Urville was posted to the Mediterranean port of Toulon, and still with a good deal of free time on his hands, he reignited his youthful interest in botany in the hills behind the port. Passions for this and other areas of science would only grow with time, and over a decade later, d'Urville's botanical work earned him membership in the Britain's Linnean Society and he became a founding member of the French Geographical Society.

In 1814, d'Urville had a brush with his future. After Napoleon's exile to the island of Elba, the Ville de Marseille (with Ensign Jules Dumont d'Urville onboard) sailed to Palermo with the Duke of Orleans, so the latter could retrieve his wife and children. The Duke was the future King Louis Philippe, who nearly a quarter-century later would sponsor d'Urville's expedition to the South Pacific—and the Antarctic. It was to be France's last great scientific expedition carried out under sail.

From 1822-25, Lieut. d'Urville circumnavigated the world as the executive officer on the Coquille during a South Seas expedition, and afterwards published a favorably received volume on the flora of the Falkland Islands. Between 1826-29, he commanded the Astrolabe (the renamed Coquille; an astrolabe is an instrument used for observing the positions of celestial bodies), tasked with augmenting the scientific knowledge amassed on the previous expedition. In his official instructions to d'Urville, Secretary of the Navy Comet de Charbol wrote:

A large collection of books, instruments and charts etc. was to have been sent to you by courtesy of the Director-General of Navy Stores.

Astrolabe expedition have recently been forwarded to you, you will be able to distribute them in the countries you visit and wherever you deem it useful to leave some mark of your passage.

Supplying such medals to exploring expeditions can be traced back for several decades before this time and includes not only French, but British and Russian expeditions as well. The medals were given to native dignitaries in silver or bronze, presumably depending upon the individuals' social/political position. The very few number of silver medals carried on the above expedition would seem to indicate such pieces were only presented to very highly placed individuals.

During the voyage, d'Urville successfully searched for the wreckage and remains of the LaPérouse expedition, which vanished 40 years before. Among the relics recovered from native peoples were some of the 100 medals carried by that expedition.

Along with the following years of domestic life and mundane naval desk duties, d'Urville devoted time to continued studies of the ethography and linguistics of South Pacific peoples. But as his research progressed, he noted missing pieces of knowledge, which could be remedied by a new expedition. By the end of February 1837, King Louis Philippe had seen and enthusiastically approved d'Urville's new expedition—but with a twist. Not only was the King interested in extending French influence and furthering hydrography, trade and science, he knew about British and American interests in the Antarctic regions, and ordered d'Urville to 'extend your exploration towards the Pole as far as the polar ice will permit.' D'Urville was also in search of another pole—the South Magnetic Pole—'the point it was so important to fix for the solution of the great problem of the laws of terrestrial magnetism.'

The King was well aware that the British Antarctic explorer and sealer James Weddell had reached 74°15'S in 1823—and now an opportunity to bring honor to France presented itself. Though d'Urville admired British polar explorers like Cook, Ross and Parry, he wrote:

Also 30 silver and 450 bronze medals that I had struck to commemorate the

I had never aspired to the honour of following in their wakes; on the contrary, I had always declared that I would prefer three years of navigation under burning equatorial skies to two months in polar climes.

Two ships would carry the flag of France to frozen shores. The Astrolabe and Zélée (zealous). The former carried 17 officers and 85 men, while the Zélée's compliment was 14 officers and 68 men (the actual number of crewmen for each ship varied over time due to those invalided, deaths, desertions and new recruits). To promote interest in the expedition's progress, d'Urville asked for and received royal approval promising monetary rewards related to degrees of southern latitude attained by the Astrolabe and Zélée. Once 75°S was reached, each man would receive 100 francs, and then 20 francs for each additional degree above this latitude. Weddell had reached 74°15'S. As d'Urville flatly stated, 'It was not much, but it was enough for the purpose.'

As with his previous voyage, d'Urville took with him a supply of silver and bronze medals with which to mark his passage throughout the southern Pacific Ocean. The 50 mm. diameter medals depict a profile of the King on the obverse, surrounded by the translated wording: LOUIS PHILIPPE I./KING OF FRANCE. Wording on the reverse specifically highlights the King's interest in Antarctic exploration. The encircling translated words read: VOYAGE AROUND THE WORLD, EXPLORATION OF THE SOUTHERN POLE, enclosing: CORVETTES/THE ASTROLABE AND THE ZÉLÉE/MR. DUCAMPE DE ROSAMEL/VICE-ADMIRAL/SECREATRY OF THE NAVY/MR. DUMONT D'URVILLE/CAPTAIN IN COMMAND OF THE EXPEDITION/MR. JACQUINOT/COMMANDER OF THE ZÉLÉE/1837.

I have yet to find any documentation noting the number of silver and bronze medals struck for the 1837-40 expedition, but feel the figures are very close (if not identical) to those for the 1826-29 voyage. A bronze medal exists that is attributed to Gunner First Class Paul Plagne (Astrolabe), who received the Legion of Honor for his performance during the expedition. This suggests that some of the leftover medals were given to certain participants as mementos of their valued efforts and many hardships endured.

The Astrolabe and Zélée twice entered Antarctic waters during their three years away from home. In January 1838, they followed Weddell's track, but the weather and ice that had been kind to that British sailor in 1823 was now unkind to the Frenchmen. He retreated north and sought respite in the South Orkney Islands, partly charting them. Upon returning south, an ice floe held the ships for five days, and it was not until 9 February that they escaped nature's grasp. Later on that month, d'Urville claimed Louis Philippe Land for his country (first charted by Bransfield in 1820 and named Trinity Land), in addition to Joinville Land (later known to be an island). The ships remained in the area of what is now the northern extreme of Graham Land on into March, surveying the discoveries, but they never got beyond 66°S. Afterwards, the expedition made for Chile with several cases of scurvy aboard each vessel. Two years later, he would again challenge the Antarctic.

Approaching Antarctica from the Australian side, by mid-January 1840, d'Urville's ships were in the midst of icebergs, as passionately related by 27-year-old Ensign Joseph Duroch of the Astrolabe:

Never shall I forget the magical spectacle that then unfolded before our eyes!

On 21 January, two boats landed on a rocky islet, a few hundred meters from the shore which d'Urvile named after his wife—Adèlie Land. The surrounding waters are now know as the Dumont d'Urville Sea. The Zélée's First Lieutenant, Joseph Du Bouzet recorded the historic occasion in his diary:

But for the awesome grandeur, we could have believed ourselves amongst the ruins of those great cities of the ancient Orient just devastated by an earthquake.

We are in fact, sailing amidst gigantic ruins, which assume the most bizzare forms: here temples, places, with shattered colonnades and magnificent arcades; further on, the minaret of a mosque, the pointed steeples of a Roman basilica...

It was nearly 9 p.m. when, to our great delight, we landed on the western part of the highest and most westerly of the little islands. Astrolabe's boat had arrived a moment before us; already the men from it had climbed up the steep sides of this rock. They hustled the penguins down, who were very surprised to find themselves so roughly dispossessed of the island of which they were the sole inhabitants. We immediately leapt ashore armed with picks and hammers. The surf made this operation very difficult. I was obliged to leave several men in the boat to keep it in place. I straight away sent one of our sailors to plant the tricolour on this land that no human before us had either seen or set foot on.

Du Bouzet further penned an insightful and hopeful observation about France's Antarctic territorial claim:

...we did not dispossess anyone, and as a result we regarded ourselves as being on French territory. There will be at least one advantage; it will never start a war against our country.

Oddly, a little over a week later, the Astrolabe had an unexpected encounter with the USS Porpoise, a brig commanded by Lieut. Cadwalader Ringgold. She was part of a six-ship squadron forming the United States Exploring Expedition (1838-42). Before leaving Hobart, Tasmania, D'Urville knew of both American and British polar expeditions. An unfortunate misunderstanding, resulting from the handling of the two vessels, caused a failure of the ships to make contact and each continued on its way. D'Urville left Antarctic waters for good without discovering the South Magnetic Pole; a series of coastal observations by the British expedition in the following two years put the Magnetic Pole well inland and nowhere near the French discoveries. Still, d'Urville had every right to be proud of his men and their significant Antarctic achievements.

After further South Pacific exploration over the next several months, the Astrolabe and Zélée arrived back in France in November 1840. D'Urville had a great many things to attend to, including 'overseeing the despatch of the numerous objects destined for the Hydrographic Office, the Museum of Natural History and the Naval Museum'. Ever mindful of his men, he officially requested from the Navy Minister at least three, and as many as six months' leave for his sailors. D'Urville also submitted a carefully drawn up list, citing those he wished to be promoted and/or decorated. These requests were immediately acted upon and resulted in the Legion of Honor being awarded to several individuals by January 1841 (see list below). In spite of not achieving the intended 75°S latitude goal, the French government awarded 15,000 gold francs to be divided among expedition members.

Instituted by Napoleon on 19 May, 1802, the Legion of Honor is still awarded for distinguished military and civil services. The order exists in five classes: Knight, Officer, Commander, Grand Officer and Grand Cross. Though certain elements of its design have varied over the many years, the Legion of Honor remains today basically as it was when Napoleon created it. The decoration issued for the French South Seas Expedition was a white enameled silver or gold badge (depending upon the class), with five rays with double points. In between the rays was a green enamel wreath of oak and laurel. The obverse center featured the effigy of King Henry IV (the first monarch of the Bourbon dynasty), and the reverse center had two crossed tricolor flags. The badge was suspended by a royal crown with a ring on top, through which passes a red ribbon.

Legion of Honor Recipients of the French South Seas & Antarctic Expedition (1837-40)

ASTROLABE

DUMONT D'URVILLE, Jules Sébastien César. Captain 1st Class. Promoted to Rear Admiral on 31 December 1840 and made an Officer of the Legion of Honor. He also received the Gold Medal of the French Geographical Society.

BARLATIER DE MAS, Lieutenant Franois Edmond Eugène.

VINCENDON DUMOULIN, Clément Adrien. Hydrographer 3rd Class & Cartographer. Took over editing the publication of the voyage after D'Urville's untimely death in 1842.

DUCORPS, Louis Jacques. Purser 3rd Class. Promoted to Purser 2nd Class, 26 December 1838 and Purser 1st Class, 2 September 1840.

HOMBRON, Jacques Bernard. Surgeon 2nd Class. Promoted Surgeon 1st Class, 11 October 1838.

DUMOUTIER, Pierre Marie Alexandre. Naturalist & Phrenologist

LE BRETON, Louis. Surgeon 3rd Class (Assistant Surgeon). He did additional duty as the expedition's Artist, replacing Ernest Auguste Goupil, who died of dysentery at Hobart, 4 January 1840.

PLAGNE, Paul. Gunner 2rd Class (petty officer). Promoted Gunner 1st Class, 1 September 1837.

ZÉLÉE

THANARON, Lieutenant Charles Jules Adolphe

JACQUINOT, Honoré, Surgeon 3rd Class (Assistant Surgeon)

AUGIAS, Pierre Joseph. Coxswain 1st Class (chief petty officer)

It is noteworthy that of the 11 recipients of the decoration, all but three were from the Astrolabe. This was probably due to the fact that the Astrolabe was d'Urville's ship and there existed a natural positive prejudice on d'Urville's part. Also, only one rating from each vessel received the Legion of Honor—both of whom were senior ratings.

The Zélée's Commander Charles Hector Jacquinot, d'Urville's closest friend and second-in-command, was not decorated. On d'Urville's recommendation, he previously received the Cross of Honor for the 1826-29 expedition, but reading between the lines of his naval service, one very much gets the sense that Jacquinot probably cared very little about medals. After d'Urville's death, he assumed overall supervision for publication of the expedition's narrative. Through sheer hard work Jacquinot eventually became a Vice Admiral. During the 1854-55 Crimean War he was in command at Piraeus, Greece (receiving the Greek Order of the Redeemer). He died soon after retiring from the Naval General Staff in 1879; in keeping with his modesty, he had requested to be buried without any fanfare or military honors.

D'Urville wrote a lengthy letter to the Secretary of the Navy in 1841, explaining why one man was specifically excluded from being recommended for the Legion of Honor; this was Surgeon 2nd Class Elie Jean Françios Le Guillou (Zélée). A detailing of this man's behavior is out of place in these writings, but suffice to say that Le Guillou was a determined man and eventually received the medal in 1860—after years of wearing down the opposition. During the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, he was the medical officer to the Corps de Francs-Tireurs (snipers). Interestingly, Cape Leguillou (note the spelling) appears on the Antarctic map to this day, located on the northern point of Tower Island, at the northeast end of the Palmer Archipelago.

After the 1837-40 expedition, with his health strained from three around-the-world voyages, D'Urville's days of exploring were behind him. He began writing up the narrative of his latest expedition, and just as the fourth volume was nearly ready for the publisher, tragedy overcame d'Urville and his family. Rear Admiral Jules Dumont d'Urville, his wife and son, were returning by train from an outing to Versailles on 8 May 1842, when the two locomotive engines jumped the track. The leading wooden carriages ran atop the engines and caught fire, and d'Urville and his family were engulfed in flames.

Astrolabe and Zélée emerging from the pack ice, Feb. 9, 1838, by Louis Le Breton.

François Edmond Eugène Barlatier de Mas. (Courtesy of E. Barlatier de Mas Santerre)

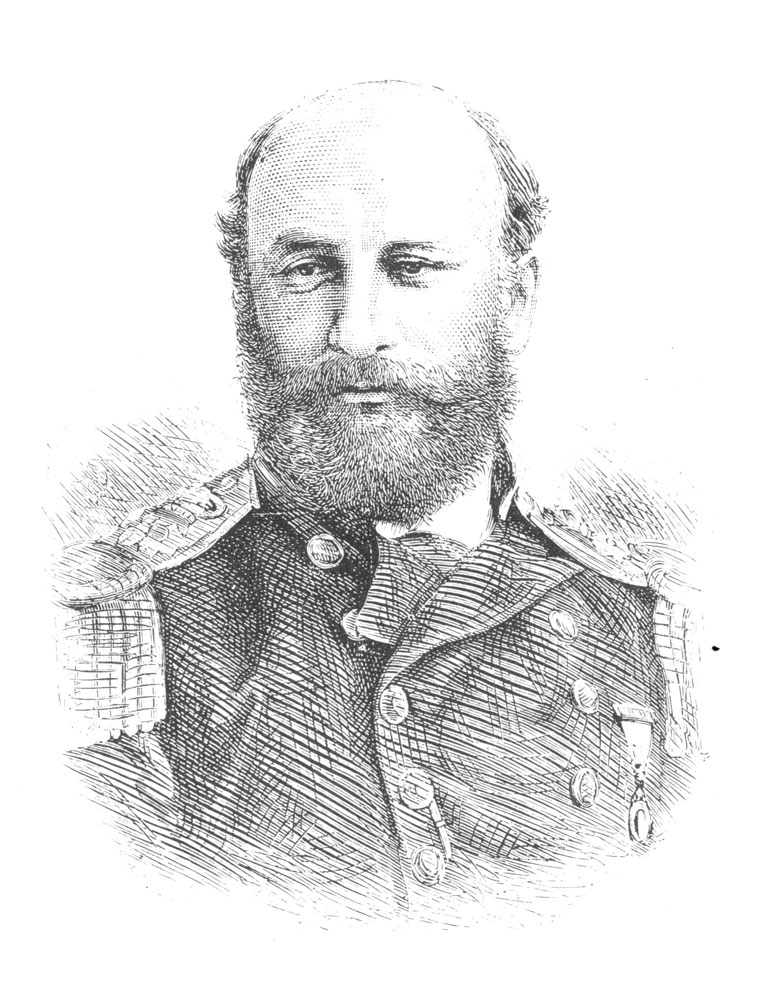

Jules Sébastien Dumont d'Urville, by Gérôme Cartellier.

Knight of the Legion of Honor (1830-48). (Courtesy of Morton & Eden Ltd.)

French South Seas & Antarctic Expedition Medal from author's collection. (Photograph by Spencer J. Fisher Photography)

Acknowledgements:

E. Barlatier de Mas Santerre

Main References:

Dr. Dominique Dirou

Michel Gontier

Morton & Eden Ltd.

Archives of the Musée de la Marine, Paris

Dorling, H. Taprell. 1974. Ribbons and Medals: The World's Military and Civil Awards. Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Dunmore, John. 1965. French Explorers of the Pacific (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Jacob, Yves. 1995. Dumont d'Urville, Le Dernier Grand Marin des Découvertes. Grenoble: Glnat

Rosenman, Helen (translator and editor). 1985. An Account in Two Volumes of Two Voyages to the South Seas by Captain (later Rear-Admiral) Jules S-C Dumont D'Urville of the French Navy, etc. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press

THE GERMAN ATLANTIC METEOR EXPEDITION MEDAL 1925-27

To reproduce or distribute, visit: gmsteinfrgs.icopyright.com

After the defeat of Germany in the First World War, the German people had little to bolster their national pride. Out of the political and economic chaos came one of the most important oceanographic expeditions of the 20th century.

In order to salvage German scientific research and the specialized knowledge and experience gained from it, the German Scientific Research Aid Council was formed in 1920 (also called the Emergency Association for German Science in some sources). The Council's task was to put public and private funds to their best possible use to this end.

In 1924, Vienna-born oceanography Professor Alfred Merz (University of Berlin) asserted that the ocean offered an open door of opportunity for exploration. Merz suggested a well-planned voyage would invite solutions to important problems of the deep. The president of the Council recognized an extraordinary opportunity and things rapidly moved forward.

Fitted with a brigatine rig to reduce reliance on fuel, the Meteor (and her specially trained crew) was chosen as the expedition ship, and commanded by Captain F. Spiess, with Merz heading the scientific team. The crew numbered 123, including 10 officers, 29 petty officers, 78 ratings and 6 civilians.

The Meteor departed in April 1925 and conducted a shakedown cruise to the Canary Islands to ensure readiness for the voyage. Afterward, a strenuous around the clock program of scientific measurements was launched: water temperatures, depths, atmospheric observations and collecting water samples and marine life.

The Meteor crisscrossed the Atlantic 14 times, from the northern tropics to Antarctica, using the ship's early sonar, profiles of the ocean floor were created between 20° N and 55° S. The ship established 310 hydrographic stations and made 67,400 depth soundings to map the topography of the ocean floor, and released over 800 observation balloons. In fact, deep water echo sounding was extensively pioneered during the expedition. An analysis of 9,400 measurements of temperature, salinity and chemical content at varying depths established the pattern of ocean water circulation, nutrient dispersal and plankton growth.

The ship's adventures in the Southern Ocean included an oceanographic profile through the Drake Passage, while sailing from Cape Horn to the South Shetland Islands (the narrowest part of the Passage); observations of the volcanic crater on Deception Island; and stations off glacier-rich South Georgia Island. The last include Moltke Harbor, a mile-wide section on the northwest side of Royal Bay. A German contingent was stationed at Royal Bay during the first International Polar Year (1882-83), in order to observe the transit of Venus.

Next came Bouvet Island, followed by a push to the Meteor's furthest south—61° 51' S. Heading north again, a notable discovery thereafter was the extension of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge around the Cape of Good Hope toward the Indian Ocean.

When the ship returned to Germany in May 1927, she had spent 512 at sea and sailed over 67,500 nautical miles. The Meteor was the first to record an entire ocean's currents and make extensive studies of surface evaporation.

In order to commemorate the successful enterprise, the Research Aid Society of German Science created a tangible mark of distinction—the German Atlantic Meteor Expedition Medal:

Obverse: The Meteor under full sail upon stylized waves. The decision to depict the ship under sail was probably an aesthetic one, as the image would have appeared somewhat bare without the spread of canvas.

Reverse: An albatross in flight, with 'DEUTSCHE ATLANTISCHE EXPEDITION METEOR 1925-27,' above and below in serifed capital letters.

Size: 41.5 mm. diameter

Weight: 25 grams

Metal: The edge is stamped 'BAYER HAUPTMÜNZAMT. FEINSILBER' (Bavarian Central Mint. Fine Silver)

Ribbon: A heavy weave in light blue, with 1 mm. dark grey and 1 mm. silver stripes side by side, at each outer edge.

NOTE: The ribbon of the medal pictured evidently has privately mounted pin brooch, but also a loop of heavy cloth sewn on the back, in order to slide the medal onto a bar with other medals. This would seem to suggest this example was awarded to a naval officer, as such a recipient would likely have possessed other awards from the First World War.

Suspension: The First Class features a gilt oak leaves suspension for naval officers and civilian scientists, while the Second Class has a silver oak leaves suspension for crewmen.

Designer: Bavarian Central Mint.

Manufacturer: Bavarian Central Mint.

Naming: The medal was issued unnamed, but it is unknown if it was issued with a certificate bearing the recipient's name and/or rank/rate/position.

Number issued: 211 (23 First Class and 188 Second Class)

Case: The case is covered with red cloth, and interior lined with black cloth, featuring a recessed space for the medal and ribbon (but no space for a pin brooch). Stamped in upper and lower case serifed gold letters on the lid is:

The German Atlantic Meteor Expedition Medal is rarely encountered, particularly in its case of issue. Considering the complement aboard the Meteor numbered 123, and 211 medals were issued, one can assume some men were switched out during the voyage due to injury/sickness. However, it appears clear that other individuals connected with the expedition, but not onboard, were also eligible. The latter is borne out in Speiss' book: 'Every member of the expedition and every crew member received a medal from the Research Aid Society of German Science as a reward.' (English translation of Spiess, p. 360).

During the period between the end of the First World War and the onset of yet another worldwide conflict, the German Atlantic Meteor Expedition was a peace victory for science, and for Germany. The resulting medal is a lasting symbol of the pursuit of knowledge, rather than discord, within Neptune's undersea domain.

'Erinnerungs-Medaille an die DEUTSCHE ATLANTISCHE EXPEDITION METEOR 1925 - 1927 überreicht von der Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft'

(Memorial Medal to those of the GERMAN ATLANTIC METEOR EXPEDITION 1925 - 1927 presented by the Emergency Association of German Science)

The survey vessel Meteor. (Spiess)

Officers and civilian scientists onboard the Meteor (with a visiting admiral). (Spiess)

An albatross with a 2.8 meter wingspan captured by crewmen. (Spiess)