ANTARCTIC FOOD & DRINK

Launched: 18 January 2010. Last updated: 4 October 2014

Odds 'n ends about food and drink in the Antarctic. This is just starting out, so more later.

You can see some images of Antarctic beer, wine and spirits up in the cloud.

Mentions of Food in books and expedition accounts.

Mentions of Alcohol in books and expedition accounts.

A book on Antarctic food

Jason Anthony's book on Antarctic food, appropriately titled Hoosh, has been published.

See the 'Antarctic Book Notes' section elsewhere on this site.

(11 December 2012)

Train Oil and Snotters: Eating Antarctic Wild Foods

Jeff Rubin authored this very interesting and thoroughly researched paper which appeared in Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture in the Winter 2003 issue (Volume 3, Number 1).

(15 August 2010; revised 27 January 2011)

POLAR JOURNEYS; THE ROLE OF FOOD AND NUTRITION IN EARLY EXPLORATION by Robert E. Feeney. Washington, D.C. and Fairbanks: American Chemical Society / University of Alaska Press ©1997. 279pp. $45 cloth/$27.95 paper. ISBN-10: 0841233497 ISBN-13: 978-0841233492

"Stupidity, arrogance, foolishness - courage, brilliance, vision. The path to scientific discovery is never straight and not always rational. Such was the path to our current understanding of modern nutrition. In Polar Journeys: The Role of Food and Nutrition in Early Exploration, Professor Feeney, a real-life polar explorer and food biochemist, does a wonderful job describing the trial and error (and sometimes irrational) approach to establishing what we now know as "recommended daily allowance" (RDA) or the basic nutritional requirements for human health. Feeney traces the course of nutrition research from early explorers who ventured onto the oceans in small ships for months and years looking for new lands and learning the hard way, the basics of human nutrition. Did you know that ship rats are a good source of vitamin C? Did you know that 165 years after British Navy doctor James Lind found that citrus fruit cured scurvy, polar explorer, Robert Scott, still believed that scurvy was caused by ptomaine poisoning? Did you know that before there was an Atkins Diet, there was the "Eskimo Diet" which consisted of 2900 calories per day - 73% fat, 26% protein and 1% carbohydrate (one of the benefits of the Eskimo Diet was nearly odorless stool). Long before there were Institution Review Boards to oversee human experimentation, explorers were using the Earth's poles as laboratories to test the very limits (and beyond) of human endurance. Hundreds of men gave their lives, often needlessly, to discover that humans need a balanced diet of protein, fat and carbohydrate, laced with just the right mix of vitamins and minerals. If you like food, adventure and a good yarn well spun, you will enjoy this book."

—Review on amazon.com

"In this unique book, distinguished biochemist Robert E. Feeney relates the history of polar exploration to the history of the science of nutrition, showing, for example, how advances in food preservation helped make possible human survival on the expeditions. The text covers the problems caused by too scant a supply of vitamins, most notably the role of diminished vitamin C in scurvy and too much of a good thing, in the case of hypervitaminosis from unknowingly overdosing on vitamin A. The author discusses also the Eskimo knowledge of foodstuffs and how the explorers learned valuable lessons from them, as well as how expedition members delayed in applying that learning because of their Eurocentric prejudices.

With extensive quotes from explorers' journals, historical menus, tables, and numerous illustrations, the author presents a vivid description of what the expeditions experienced, making a powerful case that the explorers not only traveled metaphorically on their stomachs, they lived and died by the quantity of their food and especially the quality of their nutrition."

—University of Alaska Press website.

(15 August 2010)

[Note: This is also posted in the Antarctic Books section of this site.]

An Antarctic Menu

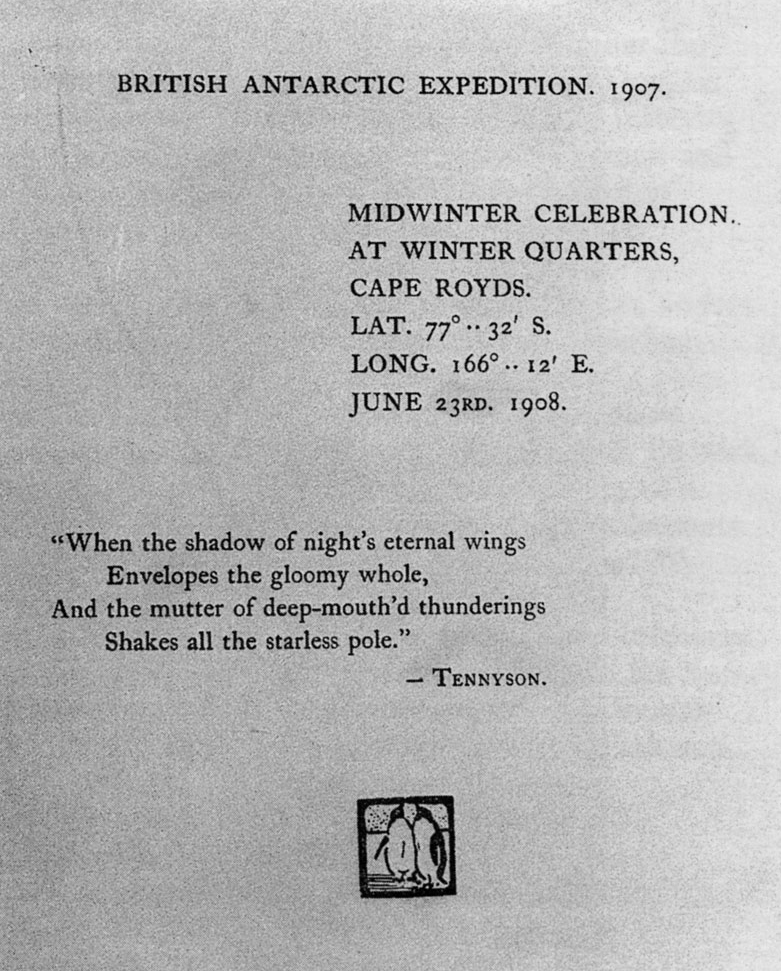

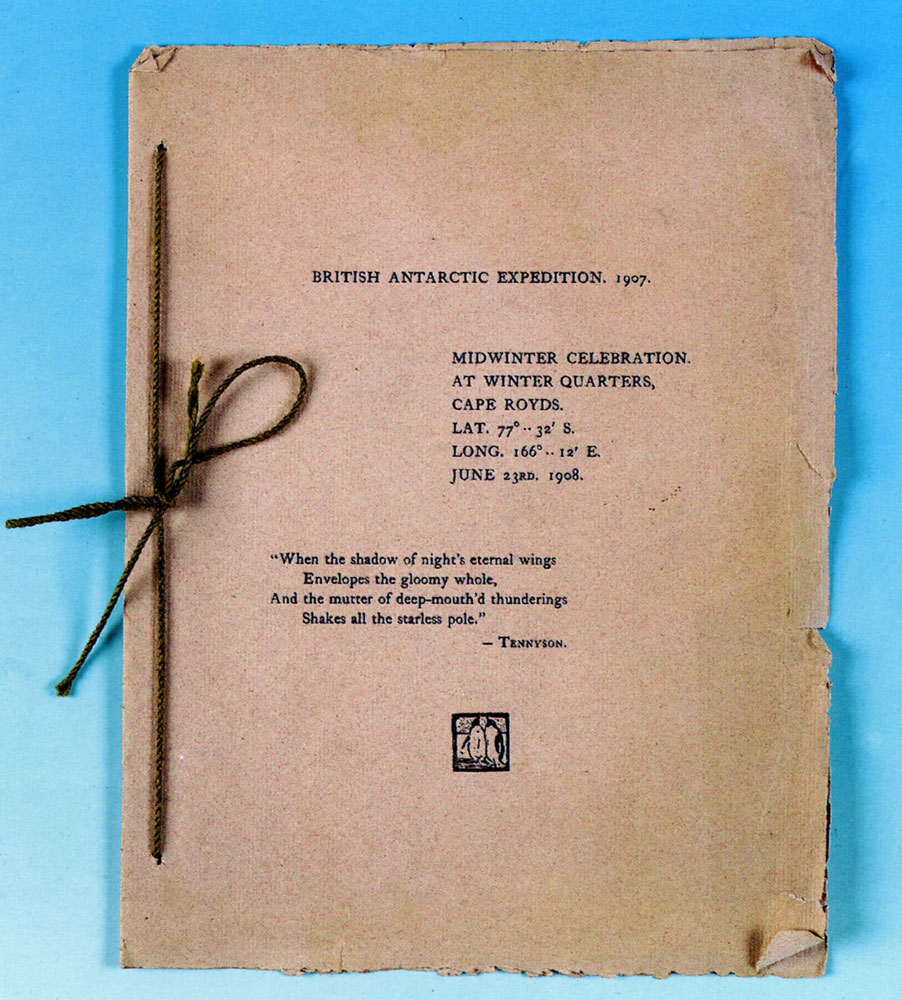

During the Heroic Age, midwinter was always celebrated with a festive dinner. One such one was held on 23 June 1908 at Shackleton's Cape Royds' hut. These dinners were usually announced by menus designed for the occasion. Some were handdrawn, some typed and at least one was printed. The significance here was that the menu was printed on the press that was used to produce the Aurora Australis and the production employed the same paper used for that rare and famous book. Occasionally the menu appears in the auction rooms. And in at least one copy of the Aurora Australis the menu (just a single sheet) is bound in at the end of the book (in the William King Davis copy at the State Library of Tasmania).

A copy was included in lot 500 sold at Webb's in Auckland on 9 December 1992. It was described thusly: "British Antarctic Expedition 1907, Midwinter Celebration, At Winter Quarters, Cape Royds, Lat. 77 deg.. 32'S;, Long. 166 deg.. 12' E;, June 23rd 1908. 'When the shadow of night's eternal wings Envelopes the gloomy whole, And the mutter of deep-mouth'd thunderings Shakes all the starless pole. - Tennysion'." The Sign of the Penguin is printed in black. Verso blank. The second leaf includes the Christmas Menu. It is possible that these 2 pages were not intended to be part of the book [Aurora Australis] but the paper and page size matches."

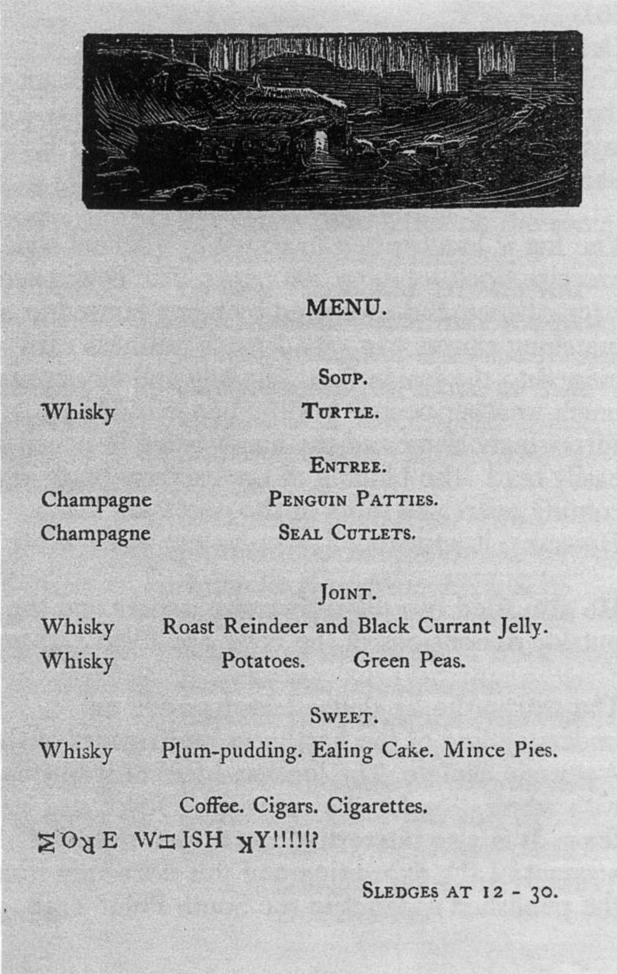

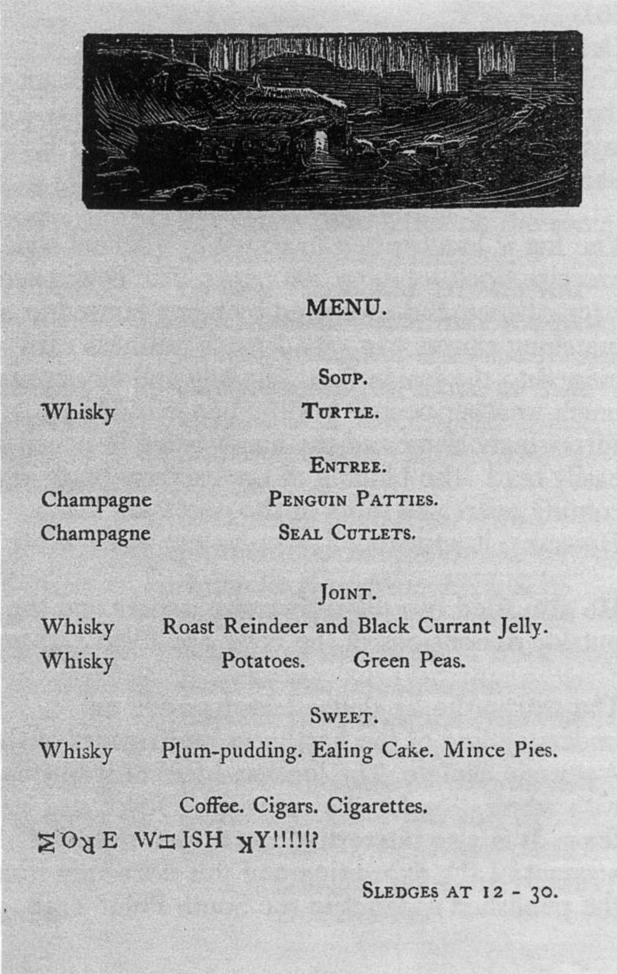

The menu features at the top an illustration by Marston.

In 2001 a stand-along copy was sold at Christie's sale 6544 at King Street, London, on 25 September (lot 54). It was described thusly:

In 2001 a stand-along copy was sold at Christie's sale 6544 at King Street, London, on 25 September (lot 54). It was described thusly:

"BRITISH ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION, 1907-1909

British Antarctic Expedition. 1907. Midwinter Celebration. At Winter Quarters, Cape Royds. Lat. 77"..32' S. Long. 166¡ .. 72' June 23rd. 1908.

[East Antarctica: printed on the Albion Press by Wild and Joyce, 1908]. 3 leaves (26 x 19cm.): blank leaf, etched plate by George Marston printed on verso of second leaf (recto blank), third leaf with text of menu headed by a woodcut vignette (verso blank). Hole-punched and tied with thin green cord within original pink paper wrappers, letterpress title printed on upper cover with 4-line quote from Tennyson and 'Two Penguins' printer's device (small clean tears to edges of wrappers).

PROVENANCE:

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (1874-1922), and thence by descent.

A VERY RARE PIECE OF EPHEMERAL PRINTING FROM THE PRESS WHICH PRODUCED THE AURORA AUSTRALIS.

'After a teetotal regime the Midwinter Day, the Great Polar Festival and Birthday festivals were a release, and an occasion for a 'wild spree'.' (Sir E.H. Shackleton, The Heart of the AntarcticT, London, 1909, I, p.216). The same volume shows a photograph of this feast, the hut interior hung with flags, facing p.224.

Estimate: £1,000-1,500 US$1,500-2,100

€1,700-2,500

The hammer price was £8500

(15 August 2010)

(15 August 2010)

Some Food-related Firsts:

First crops (mustard and cress) grown in the Antarctic. (October 1902). British National Antarctic expedition under Robert F. Scott in the Discovery.

First harvest of first crops grown in the Antarctic. (November 1, 1902). British National Antarctic expedition under Robert F. Scott in the Discovery.

First dairy cows in Antarctica. (1933-1935). Second Byrd Antarctic expedition under Richard E. Byrd. [See http://www.antarctic-circle.org/E07.htm]

(18 January 2010)

Whisky on (Antarctic) ice

Explorer Ernest Shackleton loved his Scotch whisky. And he left a stash at the bottom of the world.

By Emily Stone — Special to GlobalPost

CAPE ROYDS, Antarctica This spit of black volcanic rock that juts out along the coast of Antarctica is an inhospitable place. Temperatures drop below -50 Fahrenheit and high winds cause blinding snowstorms. The only neighbors are a colony of penguins that squawk incessantly and leave a pungent scent in their wake.

But if you happen upon the small wooden hut that sits at Cape Royds and wriggle yourself underneath, you'll find a surprise stashed in the foot and a half of space beneath the floorboards. Tucked in the shadows and frozen to the ground are two cases of Scotch whisky left behind 100 years ago by Sir Ernest Shackleton after a failed attempt at the South Pole.

Conservators discovered the wooden cases in January 2006. They were unable to dislodge the crates, but are going in with special tools in January during the Antarctic summer to try to retrieve them. An international treaty dictates that the crates, and any intact bottles that are inside, remain in Antarctica unless they need to be taken off the continent for conservation reasons. The whisky's condition after a century of freezing and thawing is unknown.

Polar explorers of that era relied on their alcohol of choice to help them and their crews through the long Antarctic nights and insomnia-inducing days. And Shackleton knew a thing or two about being well prepared for an adventure. On a later trip to the continent he kept all 28 members of his crew alive during 15 harrowing months after their ship got marooned in and then slowly devoured by ice. So it's no surprise that he brought 25 crates of Scotch with him when he set off on an expedition to the South Pole in 1907.

The earlier trip didn't go well, either. Shackleton turned around 97 miles short of his destination, telling his wife, "I thought you'd rather have a live donkey than a dead lion." When the ship arrived in 1909 to pick the men up, they left their supplies behind in their hut, including reindeer sleeping bags, tins of boiled mutton and bottled gooseberries. And, as we now know, they also abandoned two cases of Charles Mackinlay & Co. whisky.

Al Fastier is a program manager in New Zealand with Antarctic Heritage Trust, the group charged with preserving the hut at Cape Royds along with three others on that section of Antarctic coastline. He was there the day the crates were discovered. The team was clearing out a century's worth of ice that had accumulated under the hut and was causing structural problems.

"It was a very exciting time of actually finding artifacts that possibly hadn't been seen since the historic explorers left," he said. The group also found felt boots and jugs of linseed oil. The other 5,000 or so artifacts left behind are inside the hut or on the ground nearby and had been catalogued and viewed by the occasional tourist and on the internet.

In January, the conservationists will use a special drill that chips into the rock so they can pull the crates out and let them melt free in the omnipresent Antarctic summer sun.

So what will century-old, Antarctic-iced Scotch taste like?

Richard Paterson, master blender at Whyte & Mackay, the Glasgow whisky company that now owns the Mackinlay label, is eager to learn of the whisky's fate. He's equally hopeful that he gets to taste some of it.

He has a 1907 letter from Shackleton acknowledging receipt of the cases, along with a photograph of the bottles' label. The company may have donated the cases, which Paterson said cost 28 shillings each, as polar explorers came looking for sponsors for their trips, which were usually run on tight budgets. "Shackleton has been one of my heroes for many years," he said. "It's nice to think that perhaps we helped him when his other spirits were down, that our spirits kicked him up a wee bit."

Paterson said he'd expect that when bottled, the whisky was heavy and peaty, which was the style in that era. He'd like to sample it by sticking a needle through the cork and extracting some of the liquid with a syringe. If the bottles stayed airtight a big if since the corks may have shifted as they were expanding and contracting with the changes in temperature — the whisky would likely taste much as it did in Shackleton's day, Paterson said.

A whisky's flavor develops as it's aged in barrels because air is able to reach it. Once it's bottled and cut off from external oxygen, it stops changing in taste. If oxygen was sneaking back into the bottles, the whisky would have continued aging and could have started to go bad, much like food that's left out too long.

Even if the bulk of the bottles remain in Antarctica for historic reasons, Paterson is hopeful that a couple can be returned to the company. One would go in the Mackinlay family archives and the other could be auctioned off, he said.

Helen Arthur, who has written six books about whiskey from her home in southern England, said it's difficult to guess what a bottle of Shackleton's whiskey would fetch, but if it's in good shape and the label is intact, it could be upwards of $1,000. While she doubts the whisky still tastes very good, she doesn't think a buyer would be interested in it for sipping, but rather for its lineage.

If the bottles stay in the hut, which sees about 900 visitors a year, they will be protected from any over eager collectors, Fastier said. No one is allowed into the huts without a guide, and the value of an artifact often dictates how high up on a shelf it's placed.

Paterson said he'll be disappointed if that is the whiskey's final resting place.

"It's been laying there lonely and neglected," he said. "Can it not come back to Scotland where it was born?"

Source: http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/environment/090909/shackletons-whisky

Published: October 26, 2009

Thanks to Kate Pokorny